Sentenced to College - Chapter 1

The Angel Hernandez story

New here? Start from the beginning...

I first met Angel Hernandez and his wife, Lily, at a small Mexican restaurant about an hour’s drive from my home. It was a Monday—July 5, 2021—and Angel happened to have the day off from work since the Fourth of July fell on a Sunday that year, one day earlier. It was a cute and colorful restaurant right in the center of town, and with the strict COVID-19 restrictions lifted just a few months earlier, I was happy to see this small family business had survived.

When I walked in, I found Angel and Lily seated in a corner booth next to a large window. Angel stood to greet me and it was then I realized exactly how tall he was. At 6’4”, he had a commanding presence that, I assumed, would have played to his advantage back in the day. Back when he was “King Angel, head of the Latin Kings.”

“You must be Angel,” I said as I smiled and extended my hand to greet him.

“Yes, and this is my wife, Lily,” he added.

“Nice to meet you,” I said as I shook Lily’s hand and then settled into my spot across from them in the booth.

Trying not to appear nervous (which I totally was), I reached into my bag and pulled out a small digital recorder. I’d waffled over whether to even bring it, worried they might be put-off or intimidated by me wanting to record our conversation. On the other hand, I worried I might miss something if I didn’t.

“Do you mind if I record this?” I asked them. “That way I don’t have to scribble notes while we’re talking and eating.”

“Sure, that’s fine,” they graciously agreed.

As I fumbled around with the recorder trying to remember how to turn it on, I suddenly dropped the thing on the floor and had to go scrambling on my hands and knees under the table to go fetch it.

“Nice, Joy,” I thought to myself. “Real professional.”

A few months earlier, I’d been attending a Rotary meeting at The Oaks restaurant in Willmar and was seated next to Don Spilseth, a retired district judge. After 24 years on the bench, he’d retired as Chief Judge for the 8th District of Minnesota in 2017, and though many knew him as “The Honorable Donald M. Spilseth,” I just knew him as Don.

Don is a member of our Willmar Rotary Club and the best “Fine Master” our club has ever seen. In that role, it was his responsibility to raise charity funds from unwitting club members by fining us one dollar for any number of ridiculous violations—like not eating all the vegetables on our plate, not knowing what year Rotary was founded, or not remembering the final score of the 1991 World Series. All the money went to good causes and we always enjoyed Don’s rapid fire delivery and razor sharp wit.

One day, I was sitting next to Don at Rotary and decided to ask him about a court case I’d recently begun researching. I knew very few details, but recalled it had taken place during the 1990s and involved a young gang member from Willmar who had threatened a store manager. But instead of going to jail, the judge had sentenced this kid to college. People were furious about it and the story went on to make national headlines.

I’d been wondering about this guy for years and had hoped to cover his story on my blog. Whatever happened to him? Did he graduate? Where is he now? How did it all work out for him? All I could remember was that the kid’s name was Angel—a tidbit that had stuck with me because I thought it was so ironic. How funny, a gangster named Angel. I tried Googling “Angel” and “sentenced to college” but got nowhere. When I asked around, people vaguely remembered the story but couldn’t remember any details.

So I asked Don, “Do you remember that case from back in the 90s about a kid who got sentenced to college?”

Don turned to look at me like I suddenly had corn sprouts growing out of my ears.

“That was me,” he said. “I was the one who sentenced him to college!”

A few weeks later, I met Don at his house in Spicer to talk about the case. Not only did he share more about what had led him to make such a monumental court decision, Don went a step further. Using the contact information I’d managed to find for Angel after learning his last name, Don offered to call him up, explain who I was, and ask if he’d be willing to share his story with me. Angel agreed.

And now, here I was. After all that dumb luck and good fortune, I found myself crawling around on my hands and knees under a table at Mi Mexico restaurant and wondering why any of these people would be willing to talk to me at all. Using my iPhone’s flashlight, I finally spotted the recorder, grabbed it, and returned to my spot at the table.

“Sorry. Awkward.”

They laughed and I started again.

“I’d like to know more about the beginning part of your journey,” I prompted. “What was life like before all of this happened and your name was suddenly all over the headlines?”

Angel paused a moment before answering.

“At that time, I had only been back in Willmar for about… a year? Two years?” He glanced at Lily. She nodded.

“He was born in Grand Prairie, Texas, west of Dallas,” Lily said. “He was the oldest… there’s only two of them.”

It would go on like this for the next two hours—Angel answering my questions in his quiet, soft-spoken voice while Lily added details in her strong, confident voice that held little hint of an accent. As I listened and watched, I was mesmerized by the easy flow of their conversation. When one struggled to remember details, the other jumped in, and they continued to groove back and forth like this, often completing each other’s sentences without even realizing it. They were like a skilled relay team, passing the baton back and forth with mutual trust and respect.

It was then I began to realize I had stumbled upon something much deeper than an article about a landmark court case or the rise of gangs in rural Minnesota. At the heart of it all was a love story about a pair of high school sweethearts who still had each other’s backs. They had faced impossible odds throughout their young lives, but in spite of it all—the breaks, the setbacks, the brick walls, and the regrets—they were making it.

The oldest of two boys, Angel was born in Grand Prairie, Texas on April 30, 1980. Grand Prairie is a split suburb that sits midway between Dallas and Fort Worth and is situated in three different counties. With a population of 71,000 in 1980, it had traditional roots as a railroad and farming town, but was quickly growing and would have a population of 100,000 just ten years later (and over 210,000 today).

Angel doesn’t remember a lot from his early childhood. He knows that he and his family lived in the Houston area when he and his brother were both toddlers. After that, they moved back to Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, a border town on the south bank of the Rio Grande. Laredo, Texas is on the north bank.

“Everything I remember is from third grade and up,” he told me. “I don’t remember much from back then.”

“When he came to Minnesota in third grade, he didn’t speak English,” Lily added.

Angel explained that he went to three different schools in third grade—one in Mexico, one in Texas, and one in Willmar. He started school in Mexico and attended there until his family decided to move to Texas when he was in third grade. He started again in Texas, then halfway through the year, his family moved to Minnesota. That’s when he started to learn English for the first time. He completed third grade in Willmar and by fourth grade he was just starting to pick up English when his family moved back to Texas again.

Angel explained that, back in Texas, kids don’t learn English because it’s not required. So, while the rest of his classmates were all being taught in English, his teachers would give him a book in Spanish. He started to wonder how—or if—he would ever learn English.

“Down there, everything is in Spanish,” Lily explained. “Everywhere you go, it’s Spanish.”

Angel nodded. “Our community was 97% Hispanic. The only white people down there were teachers or people in charge. Everything is in Spanish—radio, TV, news. Unless you’re listening to country music, that’s probably the only thing you’re going to get in English.”

That being the case, I asked him what he thought of Willmar when he first arrived. “Was it a huge culture shock?”

“Yes,” he said quietly.

Angel was a sophomore when they moved back to Willmar, and at that time, he guessed there were maybe 20-30 Hispanic kids at the high school. (With class sizes of approximately 300, that was less than 10%.) Before that, when he came in third grade, he guessed maybe 5-10 Hispanic kids at his elementary school.

“So yeah, it was way different… adapting.”

When he and his parents first moved to Willmar, they came to work in the farm fields. His father was an alcoholic at the time and on his way to becoming a heroin addict.

“For us, growing up, it’s not like growing up white, or growing up any other kind of race,” Lily said. “There are certain expectations that our parents have for us.”

“Not just expectations but limitations, as well,” Angel added.

“Education and going to college… those aren’t aspirations that our parents had for us. For us, it was just the bare minimum. My mom hated me going to school and let me ditch whenever I wanted to. She took my brother out of school when he was in fifth or sixth grade, and that’s the highest grade he finished.”

Neither of their parents graduated from high school. Angel guessed that his parents had quit school after seventh or eighth grade. For Lily’s parents, it was even earlier. She guessed third grade for her mom and first or second grade for her dad.

“As soon as they started working, there was no more school,” Angel explained.

“It’s just work,” Lily said. “You work, and you work, and you work, and you work. That’s all you do. And, you’re always supposed to respect your elders, even if they don’t respect you.”

I asked her what she meant.

“There’s no talking back,” Angel said.

“There’s no raising your voice,” Lily added. “Even when you’re 18, 20, 30. You’re always supposed to help your parents, even when they’re wrong. Even when they’re drug addicts.”

They glanced at each other.

“There are a lot of drugs in our culture,” Angel explained. “It’s like normal. That and domestic abuse. We grew up seeing domestic abuse all the time. My dad used to beat my mom and we would have to call the cops on him. They’d come and arrest him, then he’d be gone for a while and come back. They ended up putting him in treatment in Albert Lea and then it pretty much stopped.”

“It worked?” I asked him.

“Kind of,” he replied. “Better than what it was.”

“But, for other cultures, it’s like traumatizing for a child,” Lily explained. “What we go through growing up, that’s normal. Not having anything to eat, or hot water to take a shower.”

She went on to explain that whichever kid is the oldest—even if that kid is only seven years old—they are responsible for taking care of all the younger siblings.

“I was like eight years old,” Angel told me. “And I would have to stay home and watch my kid brother who was two years younger than me. And I couldn’t open the door because my parents weren’t home. So they taught us how to cook, at least an egg, so we could make food for ourselves.”

“And he was lucky that it was just him and his brother,” Lily added.

When Angel was just eight or nine years old, his mom pulled him out of school in the spring to help clear the rocks out of the fields before planting. In order to avoid any truancy questions, Angel’s mom would just tell the school they were moving back to Texas.

Angel picked weeds and rocks—everything the adults would do—and the farmers would show them how to do it.

Lily backed him up. “It wasn’t like they said to themselves, ‘Oh, he’s a kid so he’ll do half the work.’ We were expected to do the same work as an adult was expected to do in a day.”

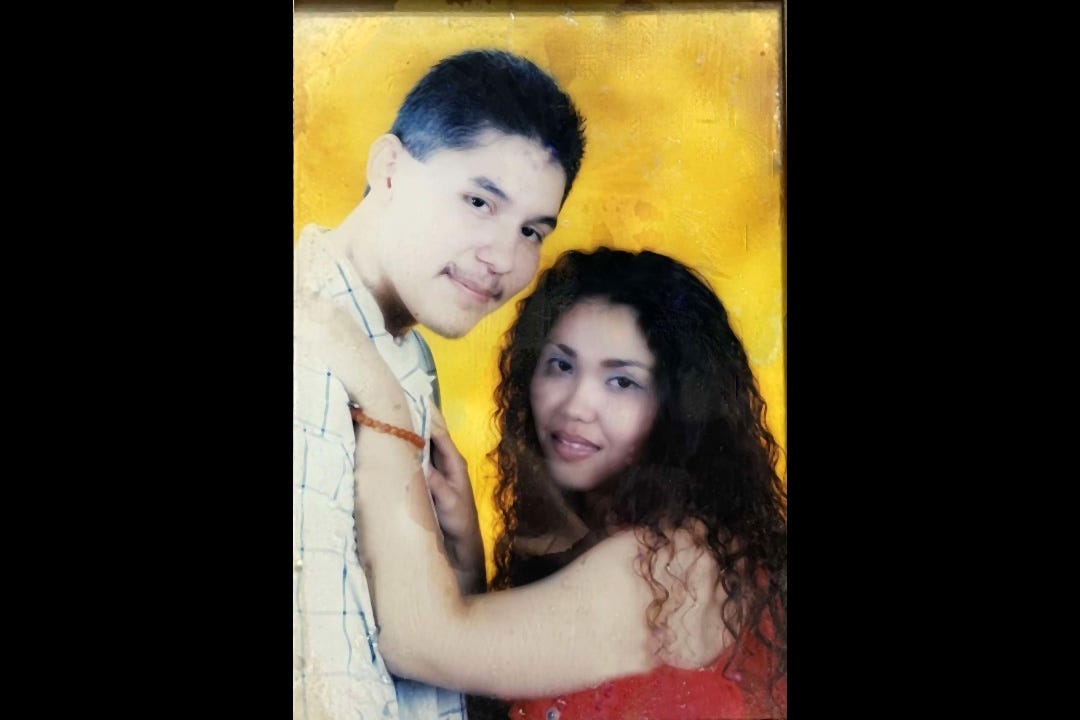

Lily first met Angel in Willmar during the spring of 1996. She also grew up in Laredo and, ironically, was in the same class as Angel’s younger brother, but they never knew each other in Texas. Instead, Lily and Angel would meet years later in a town that was 1,400 miles away and foreign to both of them.

Each summer Lily and her mom would come to Willmar to visit Lily’s older sister and stay with her for a month or two. In 1996, Lily and her mom left for Willmar in March (a few months before the school year ended in Texas), so when they arrived in Minnesota, Lily’s mom enrolled her at Willmar Middle School so she could finish out her 8th grade year. That’s when she met Angel.

Lily and Angel were both born in 1980, but since he had an April birthday and hers wasn’t until December, he was finishing 9th grade at Willmar High School while she was finishing 8th grade at the middle school. Before long, the two of them ran into each other while hanging out with friends and Angel asked her out on a date. He took her out to dinner at Happy Chef and soon they were inseparable. They went to the movies together, hung out at the arcade in the Kandi Mall, and went for rides in Angel’s 1987 Buick Somereset that he’d bought with his own money.

When summer came to an end that year, they kept in touch by sending 80-page spiral notebooks back and forth, filled with handwritten letters to each other.

“And we just kept corresponding like that,” Lily told me. “I would send him a notebook, and then he would send me a notebook back. He was a good boy when I met him. He worked and went to school. That’s all he did. He hung out with his friends, but he hadn’t been in any trouble at that point.”

They lost touch for a couple of years and it wasn’t until 1999, when Lily was in her senior year back in Texas, that she received a letter from Angel. He’d written to congratulate her because he knew she’d be graduating in a few months. And then, he shared some other news. Bad news.

Angel was in jail facing charges of attempted theft, 5th degree assault, disorderly conduct, and making terroristic threats for the benefit of a gang. If convicted, he could be sentenced up to 2 ½ years in prison.

Lily was in shock. What had happened to the good boy she had been dating just a few years earlier? What exactly was going on up in Minnesota?

Next time: A look at Willmar from 1996 to 1999

Dear Jacob: A Mother’s Journey of Hope was released on October 17th, 2023 by MNHS Press. You can purchase it at your favorite bookseller, or ask for it at your local library.

![[ j o y . t h e . c u r i o u s ]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!UzSv!,w_80,h_80,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F9a3fc6e9-2c7b-49f3-a947-5510d6ac2bd3_500x500.png)

![[ j o y . t h e . c u r i o u s ]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!RoQy!,e_trim:10:white/e_trim:10:transparent/h_72,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff10a4cb8-9c26-4c77-a86d-fd0df8c2f58f_1344x256.png)

An intriguing start to this story. I'm looking forward to hearing more about Angel and Lily, about what happened next to both of them, and about the judge who crafted Angel's unique sentence.